More than two-thirds of Americans think the Supreme Court was right to hold Harvard's race-based admissions policy unlawful. But the minority who disagree have no doubt about their own moral authority, and there's every reason to believe that they intend to undo the Court's decision at the earliest opportunity.

Which could be as soon as this year. In fact, undoing the Harvard admissions decision is the least of it. Republicans and Democrats in Congress have embraced a precooked "privacy" bill that will impose race and gender quotas not just on academic admissions but on practically every private and public decision that matters to ordinary Americans. The provision could be adopted without scrutiny in a matter of weeks; that's because it is packaged as part of a bipartisan bill setting federal privacy standards—something that has been out of reach in Washington for decades. And it looks as though the bill breaks the deadlock by giving Republicans some of the federal preemption their business allies want while it gives Democrats and left-wing advocacy groups a provision that will quietly overrule the Supreme Court's Harvard decision and impose identity-based quotas on a wide swath of American life.

This tradeoff first showed up in a 2023 bill that Democratic and Republican members of the House commerce committee approved by an overwhelming 53-2 vote. That bill, however, never won the support of Sen. Cantwell (D-WA), who chairs the Senate commerce committee. This time around, a lightly revised version of the bill has been endorsed by both Sen. Cantwell and her House counterpart, Cathy McMorris Rodgers (R-WA). The bill has a new name, the American Privacy Rights Act of 2024 (APRA), but it retains the earlier bill's core provision, which uses a "disparate impact" test to impose race, gender, and other quotas on practically every institutional decision of importance to Americans.

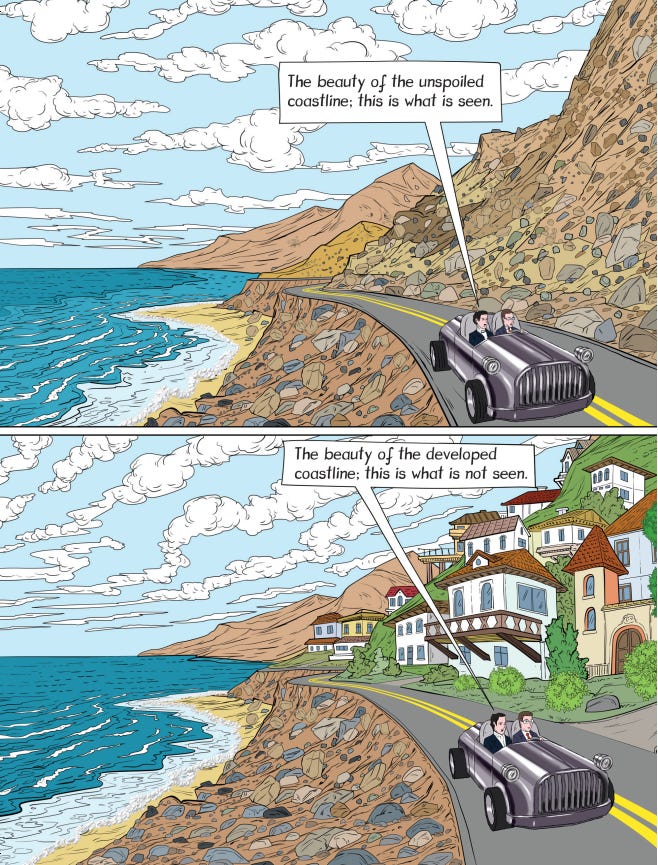

"Disparate impact" has a long and controversial history in employment law; it's controversial because it condemns as discriminatory practices that disproportionately affect racial, ethnic, gender, and other protected groups. Savvy employers soon learn that the easiest way to avoid disparate impact liability is to eliminate the disparity – that is, to hire a work force that is balanced by race and ethnicity. As the Supreme Court pointed out long ago, this is a recipe for discrimination; disparate impact liability can "leave the employer little choice . . . but to engage in a subjective quota system of employment selection." Wards Cove Packing Co. v. Atonio, 490 U.S. 642, 652-53 (1989), quoting Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 448 (1975) (Blackmun, J., concurring).

In the context of hiring and promotion, the easy slide from disparate impact to quotas has proven controversial. The Supreme Court decision that adopted disparate impact as a legal doctrine, Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 432 (1971), has been persuasively criticized for ignoring Congressional intent. G. Heriot, Title VII Disparate Impact Liability Makes Almost Everything Presumptively Illegal, 14 N.Y.U. J. L. & Liberty 1 (2020). In theory, Griggs allowed employers to justify a hiring rule with a disparate impact if they could show that the rule was motivated not by animus but by business necessity. A few rules have been saved by business necessity; lifeguards have to be able to swim. But in the years since Griggs, the Supreme Court and Congress have struggled to define the business necessity defense; in practice there are few if any hiring qualifications that clearly pass muster if they have a disparate impact.

And there are few if any employment qualifications that don't have some disparate impact. As Prof. Heriot has pointed out, "everything has a disparate impact on some group:"

On average, men are stronger than women, while women are generally more capable of fine handiwork. Chinese Americans and Korean Americans score higher on standardized math tests and other measures of mathematical ability than most other national origin groups….

African American college students earn a disproportionate share of college degrees in public administration and social services. Asian Americans are less likely to have majored in Psychology. Unitarians are more likely to have college degrees than Baptists.…

I have in the past promised to pay $10,000 to the favorite charity of anyone who can bring to my attention a job qualification that has made a difference in a real case and has no disparate impact on any race, color, religion, sex, or national origin group. So far I have not had to pay.

Id. at 35-37. In short, disparate impacts are everywhere in the real world, and so is the temptation to solve the problem with quotas. The difficulty is that, as the polls about the Harvard decision reveal, most Americans don't like the solution. They think it's unfair. As Justice Scalia noted in 2009, the incentives for racial quotas set the stage for a "war between disparate impact and equal protection." Ricci v. DeStefano, 557 U.S. 557, 594 (2009).

Not surprisingly, quota advocates don't want to fight such a war in the light of day. That's presumably why APRA obscures the mechanism by which it imposes quotas.

Here's how it works. APRA's quota provision, section 13 of APRA, says that any entity that "knowingly develops" an algorithm for its business must evaluate that algorithm "to reduce the risk of" harm. And it defines algorithmic "harm" to include causing a "disparate impact" on the basis of "race, color, religion, national origin, sex, or disability" (plus, weirdly, "political party registration status"). APRA Sec. 13(c)(1)(B)(vi)(IV)&(V).

At bottom, it's as simple as that. If you use an algorithm for any important decision about people—to hire, promote, advertise, or otherwise allocate goods and services—you must ensure that you've reduced the risk of disparate impact.

The closer one looks, however, the worse it gets. At every turn, APRA expands the sweep of quotas. For example, APRA does not confine itself to hiring and promotion. It provides that, within two years of the bill's enactment, institutions must reduce any disparate impact the algorithm causes in access to housing, education, employment, healthcare, insurance, or credit.

No one escapes. The quota mandate covers practically every business and nonprofit in the country, other than financial institutions. APRA sec. 2(10). And its regulatory sweep is not limited, as you might think, to sophisticated and mysterious artificial intelligence algorithms. A "covered algorithm" is broadly defined as any computational process that helps humans make a decision about providing goods or services or information. APRA, Section 2 (8). It covers everything from a ground-breaking AI model to an aging Chromebook running a spreadsheet. In order to call this a privacy provision, APRA says that a covered algorithm must process personal data, but that means pretty much every form of personal data that isn't deidentified, with the exception of employee data. APRA, Section 2 (9).

Actually, it gets worse. Remember that some disparate impacts in the employment context can be justified by business necessity. Not under APRA, which doesn't recognize any such defense. So if you use a spreadsheet to rank lifeguard applicants based on their swim test, and minorities do poorly on the test, your spreadsheet must be adjusted until the scores for minorities are the same as everyone else's.

To see how APRA would work, let's try it on Harvard. Is the university a covered entity? Sure, it's a nonprofit. Do its decisions affect access to an important opportunity? Yes, education. Is it handling nonpublic personal data about applicants? For sure. Is it using a covered algorithm? Almost certainly, even if all it does is enter all the applicants' data in a computer to make it easier to access and evaluate. Does the algorithm cause harm in the shape of disparate impact? Again, objective criteria will almost certainly result in underrepresentation of various racial, religious, gender, or disabled identity groups. To reduce the harm, Harvard will be forced to adopt admissions standards that boost black and Hispanic applicants past Asian and white students with comparable records. The sound of champagne corks popping in Cambridge will reach all the way to Capitol Hill.

Of course, Asian students could still take Harvard to court. There is a section of APRA that seems to make it unlawful to discriminate on the basis of race and ethnicity. APRA Sec. 13(a)(1). But in fact APRA offers the nondiscrimination mandate only to take it away. It carves out an explicit exception for any covered entity that engages in self-testing "to prevent or mitigate unlawful discrimination" or to" diversify an applicant, participant, or customer pool." Harvard will no doubt say that it adopted its quotas after its "self-testing" revealed a failure to achieve diversity in its "participant pool," otherwise known as its freshman class.

Even if the courts don't agree, the Federal Trade Commission can ride to the rescue. APRA gives the Commission authority to issue guidance or regulations interpreting APRA – including issuing a report on best practices for reducing the harm of disparate impact. APRA Sec. 13(c)(5)&(6). What are the odds that a Washington bureaucracy won't endorse race-based decisions as a "best practice"?

It's worth noting that, while I've been dunking on Harvard, I could have said the same about AT&T or General Electric or Amazon. In fact, big companies with lots of personal data face added scrutiny under APRA; they must do a quasipublic "impact assessment" explaining how they are mitigating any disparate impact caused by their algorithms. That creates heavy pressure to announce publicly that they've eliminated all algorithmic harm. That will be an added incentive to implement quotas, but as with Harvard, many big companies don't really need an added incentive. They all have active internal DEI bureaucracies that will be happy to inject even more race and gender consciousness into corporate life, as long the injection is immune from legal challenge.

And immune it will be. As we've seen, APRA provides strong legal cover for institutions that adopt quota systems. And I predict that, for those actually using artificial intelligence, there will be an added layer of obfuscation that will stop legal challenges before they get started. It seems likely that the burden of mitigating algorithmic harm will quickly be transferred from the companies buying and using algorithms to the companies that build and sell them. Algorithm vendors are already required by many buyers to certify that their products are bias-free. That will soon become standard practice. With APRA on the books, there won't be any doubt that the easiest and safest way to "eliminate bias" will be to build quotas in.

That won't be hard to do. Artificial intelligence and machine learning vendors can use their training and feedback protocols to achieve proportional representation of minorities, women, and the disabled.

During training, AI models are evaluated based on how often they serve up the "right" answers. Thus, a model designed to help promote engineers may be asked to evaluate the resumes of actual engineers who've gone through the corporate promotion process. Its initial guesses about which engineers should be promoted will be compared to actual corporate experience. If the machine picks candidates who performed badly, its recommendation will be marked wrong and it will have to try again. Eventually the machine will recognize the pattern of characteristics, some not at all obvious, that make for a promotable engineer.

But everything depends on the training, which can be constrained by arbitrary factors. A company that wanted to maximize two things—the skill of its senior engineers and their intramural softball prowess—could easily train its algorithm to downgrade engineers who can't throw or hit. The algorithm would eventually produce the best set of senior managers consistent with winning the intramural softball tournament every year. Of course, the model could just as easily be trained to produce the best set of senior engineers consistent with meeting the company's demographic quotas. And the beauty from the company's point of view is that the demographic goals never need to be acknowledged once the training has been completed – probably in some remote facility owned by its vendor. That uncomfortable topic can be passed over in silence. Indeed, it may even be hidden from the company that purchases the product, and it will certainly be hidden from anyone the algorithm disadvantages.

To be fair, unlike its 2023 predecessor, APRA at least nods in the direction of helping the algorithm's victims. A new Section 14 requires that institutions tell people if they are going to be judged by an algorithm, provide them with "meaningful information" about how the algorithm makes decisions, and give them an opportunity to opt out.

This is better than nothing, for sure. But not by much. Companies won't have much difficulty providing a lot of information about how its algorithms work without ever quite explaining who gets the short end of the disparate-impact stick. Indeed, as we've seen, the company that's supposed to provide the information may not even know how much race or gender preference has been built into its outcomes. More likely it will be told by its vendor, and will repeat, that the algorithm has been trained and certified to be bias-free.

What if a candidate suspects the algorithm is stacked against him? How does section 14's assurance that he can opt out help? Going back to our Harvard example, suppose that an Asian student figures out that the algorithm is radically discounting his achievements because of his race. If he opts out, what will happen? He won't be subjected to the algorithm. Instead, presumably, he'll be put in a pool with other dissidents and evaluated by humans—who will almost certainly wonder about his choice and may well presume that he's a racist. Certainly, opting out provides the applicant no protection, given the power and information imbalance between him and Harvard. Yet that is all that APRA offers.

Let's be blunt; this is nuts. Overturning the Supreme Court's Harvard admissions decision in such a sneaky way is bad enough, but imposing Harvard's identity politics on practically every part of American life—housing, education, employment, healthcare, insurance, and credit for starters – is worse. APRA's effort to legalize, if not mandate, quotas in all these fields has nothing to do with privacy. The bill deserves to be defeated or at least shorn of sections 13 and 14.

These are the provisions that I've summarized here, and they can be excised without affecting the rest of the bill. That is the first order of business. But efforts to force quotas into new fields by claiming they're needed to remedy algorithmic bias will continue, and they deserve a solution bigger than defeating a single bill. I've got some thoughts about ways to legislate protection against those efforts that I'll save for a later date. For now, though, passage of APRA is an imminent threat, particularly in light of the complete lack of concern expressed so far by any member of Congress, Republican or Democrat.

I have recently come across two remarkable resources for any of you who are, like me, fascinated [perhaps to the point of obsession] by the early history of rock-and-roll.

I have recently come across two remarkable resources for any of you who are, like me, fascinated [perhaps to the point of obsession] by the early history of rock-and-roll.

Show Comments (9)